Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 03-04-2017

Case Style:

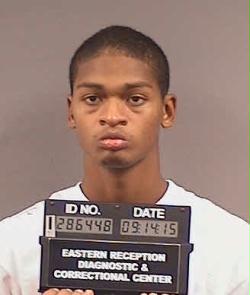

STATE OF MISSOURI vs. TAJEAON RUCKER

|

|

Case Number: ED103440

Judge: Colleen Dolan

Court: MISSOURI COURT OF APPEALS EASTERN DISTRICT

Plaintiff's Attorney:

Gregory L. Barnes

Defendant's Attorney:

Andrew E. Zleit

Description:

MoreLaw Receptionist Services

Never Miss Another Call With MoreLaw's Receptionists Answering Your Calls

From December 31, 2013 until January 2, 2014, A.G. (“Victim”) and her sister K.G.

(“Sister”) were staying at their grandmother’s house with several other family members. At that

time, Victim was ten years old and Sister was seven years old. At some point during their stay,

Victim and Sister were watching a movie in their grandmother’s basement, and Defendant joined

them. Victim alleged Defendant forced her to kiss him on the mouth, and he also rubbed her

vagina with his hand. Victim testified that she informed her sisters, mother, uncle, grandmother,

police, a social worker from Cardinal Glennon Hospital, and a forensic interviewer about

Defendant’s conduct. Sister was an eyewitness to the incident, and she testified that Victim’s

retelling of the events was accurate.

b. Prior Sexual Contact with Victim

On a previous occasion in 2011, Defendant also allegedly engaged in sexual conduct with

Victim. Sister testified that she witnessed this occurrence too. As a result of the 2011 incident,

both girls went to counseling and Defendant was told not to contact Victim. During Victim’s

testimony on direct, she stated that she told her mom she was uncomfortable around Defendant

because of “what he did to [her]” in 2011, and she was afraid Defendant would subject her to

inappropriate sexual conduct again. Victim’s mother also testified about the 2011 incident. She

testified that she told Defendant she did not want him coming into contact with Victim after she

found out he was “rubbing on her” and “touching her” on one occasion in 2011. Defense counsel

did not object to the prosecution’s questioning of Victim, her sister, or her mother about the 2011

incident, nor did counsel object to any of their testimony.

Before the start of closing arguments, the prosecution asked the trial court if it could use

evidence of the 2011 incident (1) to suggest his prior conduct made it more likely that the

allegations that Defendant’s charges were based on actually occurred (i.e., character propensity

evidence); and/or (2) to establish Defendant’s “motive” for assaulting and molesting Victim and

“intent” to do so for the purpose of sexual gratification. Defense counsel objected to the

prosecution’s use for any purpose at that point. However, the trial court informed the prosecution

that discussing Defendant’s prior sexual contact with Victim was permissible for the purpose of

establishing motive and intent, appearing to impliedly prohibit a character propensity argument.2

During closing arguments, the prosecution only referred to the 2011 incident by stating:

Let me be clear. You do get to consider the prior allegations involving [Defendant]. That gets to weigh on your verdict today, ladies and gentlemen. Yes, that goes to the elements of this case. It's not something that you have to set aside. That is something that gets to factor in your decision in finding the defendant guilty. That is what the law says.

Based on the prosecution’s use of Defendant’s prior conduct, Defendant appeals

the trial court’s judgment and asks us to reverse and remand the case for a new trial.

II. Standard of Review

Defendant concedes that his trial counsel failed to object to evidence of the alleged prior

sexual offense, and his counsel only objected to the use of such evidence just before the

prosecution’s closing argument. Accordingly, the defense counsel’s objection to the evidence

was “untimely,” as she did not raise the objection “contemporaneously” with the evidence

elicited. “A contemporaneous objection at the time of the statement [is] required in order to

preserve the issue on appeal.” State v. Thompson, 401 S.W.3d 581, 590 (Mo. App. E.D. 2013).

Accordingly, Defendant failed to preserve the issue on appeal, and “the question raised on appeal

is whether the trial court plainly erred” and caused “a manifest injustice or miscarriage of

justice.” Id.; Rule 30.20.3

We review plain error under Rule 30.20 using a two prong-standard: (1) we determine

whether the trial court erred in an “evident, obvious, and clear” manner; (2) we determine if the

error resulted in a manifest injustice or miscarriage of justice. State v. Ray, 407 S.W.3d 162, 170

(Mo. App. E.D. 2013). We use plain error review “sparingly” and the defendant bears the burden

of satisfying the two-prong test. Id.; State v. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d 753, 769-70 (Mo. banc 1996).

III. History of Using Character Propensity Evidence for Crimes Sexual in Nature

In 1995, § 566.0254 became effective and permitted the prosecution to present “evidence

that the defendant committed other charged or uncharged crimes of sexual nature involving

victims under fourteen years of age…for the purpose of showing the propensity of the defendant

to commit the crime or crimes with which he or she is being charged.” Section 566.025 was an

exception to the general rule prohibiting the prosecution from using evidence of a defendant’s

prior misconduct to prove he was more predisposed to commit the offense(s) charged. See State

v. Peal, 393 S.W.3d 621, 627-28 (Mo. App. W.D. 2013) (citing Mo. Const. art. I, §§ 17, 18(a)

(explaining a defendant may only be tried for the offenses for which he is on trial)). However,

the statute was declared unconstitutional by our Supreme Court in 2007. State v. Ellison, 239

S.W.3d 603, 607-08 (Mo. banc 2007). Our Supreme Court reasoned:

In holding [§ 566.025] unconstitutional, this Court acts consistently with a long line of cases holding that the Missouri constitution prohibits the admission of previous criminal acts as evidence of a defendant’s propensity. Evidence of prior uncharged misconduct is inadmissible for the sole purpose of showing the propensity of the defendant to commit such acts. Our cases likewise hold that convictions, as well as uncharged acts, are inadmissible to show propensity.

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 17 and 18(a) of this article to the contrary, in prosecutions for crimes of a sexual nature involving a victim under eighteen years of age, relevant evidence of prior criminal acts, whether charged or uncharged, is admissible for the purpose of corroborating the victim’s testimony or demonstrating the defendant’s propensity to commit the crime with which he or she is presently charged. The court may exclude relevant evidence of prior criminal acts if the probative value of the evidence is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice.

Mo. Const., art. I, § 18(c) (emphasis added).

IV. Discussion

Defendant argues his right to due process and his right to a fair trial—as guaranteed by

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and article I, sections 10,

17, and 18(a) of the Missouri Constitution—were violated because (1) the recently enacted

article I, section 18(c) of the Missouri Constitution cannot apply to this case because the crimes

were allegedly committed before its effective date, and the amendment may only be applied

prospectively; (2) there are no applicable case law exceptions to the prohibition of prior bad acts

evidence; and (3) even if article I, section 18(c) was applicable, the trial court erred in applying

it, as the prejudicial effect of the prior alleged sexual offense evidence plainly substantially

outweighed the probative value of the evidence. We find all of Defendant’s arguments

unavailing.

a. Missouri’s Constitutional Amendment in Article I, Section 18(c)

To address Defendant’s first point on appeal, we must first determine whether article I,

section 18(c) may apply to crimes committed before December 4, 2014, when it became

effective. The relevant timeline of the events unfolded as follows:

1. December of 2013 or January of 2014: the alleged underlying conduct for Defendant’s charges occurred;

2. December 4, 2014: article I, section 18(c) became effective; and

3. June 9-10, 2015: Defendant’s trial was held.

Constitutional amendments, just like statutory amendments, “apply only prospectively in

all but the most extraordinary circumstances.” State ex rel. Tipler v. Gardner, No. SC 95655,

2017 WL 405805, at *2 (Mo. banc Jan. 31, 2017). Accordingly, if the amendment only applies to

crimes committed after December 4, 2014, then its application would be retroactive in this case,

and we will only consider the relevant precedent at the time of the alleged conduct (most

notably, Ellison). However, if the amendment applies to any trials that begin on or after

December 4, 2014, then its application in this case would be prospective, and article I, section

18(c) may impact the admissibility of evidence.

Tipler, an opinion recently handed down by the Supreme Court of Missouri, is

controlling on this issue: “[T]he new rule of evidence adopted in article I, section 18(c) applies to

all trials occurring on or after December 4, 2014, when this new provision took effect.” Tipler,

2017 WL 405805, at *2. Our Supreme Court concluded the date of the trial controls on this issue.

Id. at *3 (“Accordingly, to say that article I, section 18(c) applies only prospectively is to say that

it applies only to trials occurring on or after its effective date.”). The Court reasoned that article

I, section 18(c) pertains to “prosecutions,” not the underlying “conduct” leading to a prosecution.

Id. at *5. Accordingly, the amendment shall be prospectively applied to any “prosecutions”

beginning on or after the amendment’s effective date of December 4, 2014.6 Id. Defendant’s trial

began on June 9, 2015.

In light of the holding in Tipler, Defendant’s argument that applying the amendment

would violate the prohibition against ex post facto laws is also unpersuasive. “It is an exercise of

the power of the state to provide methods of procedure in [its] courts.” Id. at *4 (emphasis

added). No vested right of a defendant is disturbed by laws affecting the methods of court

procedure. Id. Accordingly, “[a]s to all trials occurring after [a procedural law’s] enactment, it

[is] prospective, and not retroactive,” and “such legislation is not ex post facto.” Id.

Based on the Supreme Court of Missouri’s recent holding in Tipler, article I, section

18(c) was effective at the time of Defendant’s trial. Thus, the trial court did not plainly err by

admitting evidence of Defendant’s prior bad acts for character propensity purposes.

4. Was the Evidence’s Probative Value Substantially Outweighed by the Danger of Unfair Prejudice?

Defendant also argues that even if article I, section 18(c) was in effect at the time of his

trial, the trial court clearly erred by not excluding the evidence of his prior criminal acts because

its prejudicial value substantially outweighed the evidence’s probative value. Although the

amendment generally permits “relevant evidence of prior criminal acts” when a defendant is

being prosecuted for a “crim[e] of a sexual nature involving a victim under eighteen years of

age…The court may exclude relevant evidence of prior criminal acts if the probative value of the

evidence is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice.” Mo. Const. art I, § 18(c)

(emphasis added). We review “the trial court’s interpretation of the Missouri Constitution de

novo.” Gray v. Taylor, 368 S.W.3d 154, 155 (Mo. banc 2012). The General Assembly’s use of

the word “may” indicates that the court has discretion to exclude such evidence in these

circumstances, but it is not obligated to do so. Wolf v. Midwest Nephrology Consultants, PC.,

487 S.W.3d 78, 83 (Mo. App. W.D. 2016) (“It is the general rule that in statutes the word ‘may’

is permissive only, and the word ‘shall’ is mandatory.”). Accordingly, even if the evidence’s

probative value was “substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice,” the trial court

was not required to exclude the evidence.

“Generally, evidence of other uncharged crimes or prior misconduct is logically relevant

when it tends to establish: (1) motive, (2) intent, (3) absence of mistake or accident, (4) a

common scheme or plan, or (5) the identity of the person charged.” State v. Austin, 411 S.W.3d

284, 294 (Mo. App. E.D. 2013). The relevance of the evidence in question is clear in this case.

The evidence presented at Defendant’s trial involved his prior criminal sexual acts

against the same child. “Prior sexual conduct by a defendant toward the victim is admissible as it

tends to establish a motive, that is satisfaction of defendant’s sexual desire for the victim.” State

v. Primm, 347 S.W.3d 66, 70 (Mo. banc 2011). Furthermore, the State was required to show

Defendant’s “[i]ntent to cause sexual arousal or gratification” to obtain a conviction. See A.B. v.

Juvenile Officer, 447 S.W.3d 799, 804 (Mo. App. W.D. 2014); see also § 566.010(3).7 Defendant

was charged with first-degree child molestation under § 566.067 and third-degree assault under §

565.070. An individual commits the offense of child molestation in the first degree if (1) he or

she subjects another person less than fourteen years of age to (2) sexual contact. § 566.067 At the

time of the underlying criminal conduct, Victim was 10 years old. “Sexual contact” means “any

touching of another person with the genitals or any touching of the genitals or anus of another

person, or the breast of a female person, or such touching through the clothing, for the purpose of

arousing or gratifying sexual desire of any person.” Section 566.010(3). In Defendant’s case, the

evidence of his alleged prior sexual offenses involved the same victim as the charges before the

trial court. The evidence is especially probative to establish Defendant was sexually attracted to

Victim, which helps establish motive and intent. To whatever extent Defendant was prejudiced

by the evidence of his alleged prior sexual offenses, it did not “substantially outweigh” the

evidence’s probative value.

Defendant argues that the evidence cannot be used to show “motive” or “intent,” because

the general exceptions to prohibiting evidence of prior bad acts are only triggered when

Defendant puts these at issue, and he did not do so in this case. To support his argument,

Defendant relies on State v. Howery. 427 S.W.3d 236, 252 (Mo. App. E.D. 2014). In Howery,

this Court noted that “[i]n cases of murder or assault, prior misconduct by the defendant toward

the victim is logically relevant to show motive, intent, or absence of mistake or accident,”

however, these exceptions only apply when a defendant puts one of those at issue. Id. (emphasis

added). The rationale behind requiring the defendant to first put motive, intent, or absence of

mistake or accident at issue is “the prejudicial effect of admitting the evidence is substantial.” Id.

However, as our Supreme Court has explained, “[n]umerous cases in Missouri involving sexual

crimes against a child have held that prior sexual conduct by a defendant toward the victim is

admissible as it tends to establish a motive, that is satisfaction of defendant's sexual desire for the

victim.” Primm, 347 S.W.3d at 70. In State v. Sprofera, the Western District followed Primm in

admitting evidence of prior sexual acts against a child for the purpose of establishing motive. 427

S.W.3d 828, 835 (Mo. App. W.D. 2014). Primm and Sprofera are consistent with Missouri

courts’ greater willingness to allow evidence of prior sexual acts in sex crimes, especially prior

sexual acts committed against children. As our Court explained State v. Loazia, “[c]urrently, the

trend is toward the liberal admission of prior sex crimes under one of the stated

exceptions…[w]here a defendant is charged with committing a sexual crime against a child,

evidence of acts of sexual misconduct committed at other times by defendant against the same

victim is generally admissible.” 829 S.W.2d 558, 567 (Mo. App. E.D. 1992).Our Court’s finding

in Loazia is consistent with the enactment of article I, section 18(c), which explicitly limits the

admissibility of prior bad acts evidence to sexual crimes committed against children. Moreover,

the facts in this case are significantly more analogous to the facts in Primm and Sprofera than

Howery, where neither the crime at issue nor the defendant’s prior bad acts involved sexual

conduct.

Additionally, the new amendment allows legally relevant evidence of this type to be

admitted “for the purpose of corroborating the victim’s testimony” and for “demonstrating the

defendant’s propensity to commit the crime with which he or she is presently charged.” Mo.

Const., art. I, §18(c). In the present case, Victim testified about the crime Defendant was being

charged with, as well as his prior uncharged criminal sexual acts. The evidence of these prior

criminal acts was also relevant to corroborate Victim’s testimony that Defendant forced her to

kiss him on the mouth and rubbed her vagina at some point on the weekend of December 31,

2013 through January 2, 2014.

Accordingly, the considerable amount of probative value stemming from the evidence of

Defendant’s prior criminal acts was not substantially outweighed by any prejudicial effect it may

have had. The trial court did not plainly err in admitting evidence of Defendant’s prior sexual

acts.

Outcome: For the foregoing reasons, we affirm the trial court.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: