Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 02-20-2019

Case Style:

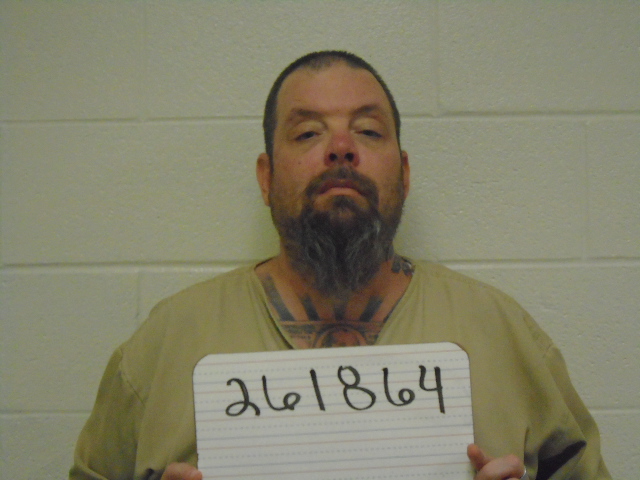

PERRY JACK PROBUS JR. V. COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

Case Number: 2018-SC-000019-MR

Judge: John D. Minton Jr.

Court: Kentucky Supreme Court

Plaintiff's Attorney: Andy Beshear

Attorney General of Kentucky

Courtney Hightower

Assistant Attorney General

Defendant's Attorney: Emily Holt Rhorer

Assistant Public Advocate

Description:

Tammy Robinson was working as a nanny when at mid-morning she

answered a knock at the door. There stood a man later identified as Solomon

Slinker. He was dressed as a deliveryman and claimed he had a package for the

homeowner, “Billy.” Slinker asked Robinson for a signature, so Robinson went

to find a pen.

As Robinson returned to the door, she found Slinker inside the house

pointing a gun at her. After a brief struggle, Slinker subdued Robinson. .

Robinson told Slinker to take whatever he wanted but not to harm Billy’s two

children, who were also in the house at the time. Slinker tied Robinson’s hands

together with zip-ties, but she broke free when one of the children ran to her.

Slinker then pushed Robinson and the child into the bathroom and followed

them inside the bathroom. While inside the bathroom, Robinson heard drilling

and banging coming from inside the house, prompting her to conclude that

another person had entered the house and was making those noises.

Eventually, Slinker left the bathroom, and Robinson retrieved her cell

phone and called for help. Robinson did not encounter any other intruder after

Slinker left the bathroom. Sergeant Ray Whitehill arrived, and his investigation

revealed, among other things of interest, a blue U-Haul blanket covering a safe

in the garage. Sergeant Whitehill later found out that the safe had been moved

to the garage from the master bedroom.

Sergeant Whitehill then spoke with Robinson, Billy, and some neighbors.

Of note, one of the neighbors recalled seeing a white Ford F-150 in Billy’s

2

driveway. After speaking with these individuals, Sergeant Whitehill received a

call from Kathy Hatcher.

Hatcher asked if there had been a home invasion “the other night” in the

neighborhood. Hatcher stated that her son, Slinker, may have been involved.

Hatcher told Sergeant Whitehill that her husband overheard Slinker’s phone

conversation in which Slinker stated that he and “P.J.” had “made the news”

but were unable to get the safe. Hatcher’s husband identified “P.J.” as the

defendant in this case, Perry Jack Probus.

Sergeant Whitehill arrested Slinker on an outstanding warrant for an

unrelated crime. Sergeant Whitehill took that opportunity to interview Slinker

about the home invasion, and Slinker admitted to the crime and implicated

Probus. Slinker gave an account of the events surrounding the home invasion.

Slinker and Probus had become housemates earlier in the month.

Slinker learned of a failed invasion of Billy’s home that Probus and an

individual named Steven Vaughan had attempted. Slinker offered to help

Probus make another attempt at the home invasion.

Probus showed Slinker Robinson’s Facebook picture and told Slinker

that Robinson would be the one answering the front door of Billy’s residence.

Probus apparently told Slinker that Billy would pay them $3500 to take a safe

from the house or $1000 to retrieve paperwork out of the safe if they could not

take the safe.1

1 Although initially suspected, police eventually stopped pursuing Billy as a suspect.

3

The evening before the home invasion, Probus sent Slinker a text telling

him to be ready the following morning. Later, on the morning of the invasion,

Probus texted Slinker, telling him to get ready. Slinker dressed as a UPS

deliveryman. Probus brought the white F-150 truck to be used in the home

invasion, while Slinker brought zip-ties, a cellphone jammer, walkie-talkies, a

clipboard, and a box. At the suggestion of Probus, Slinker also brought a BB

gun with the orange tip removed.

Probus and Slinker arrived at Billy’s residence and the events with

Robinson transpired as described above. As Slinker guarded Robinson and the

child inside the bathroom, Probus signaled for Slinker to exit the house and

return to the truck. Slinker saw that Probus had not retrieved the safe and

asked Probus about it. Probus responded that the safe was too heavy but both

would still be paid.

Upon arriving at Probus’s house, Probus told Slinker to leave and lay low

for a while. When Slinker asked Probus about the money, Probus told Slinker

that he had retrieved some laptops and purses that they could sell and split

the proceeds.

Because of Slinker’s confession, Sergeant Whitehill obtained a search

warrant for Probus’s residence where he collected several Coach purses,

(identified as belonging to Billy’s girlfriend who resided at Billy’s home), walkie-

talkies, a cell phone jammer, two U-Haul blankets, and other various items of

interest.

4

Probus was indicted. After two mistrials, at Probus’s third trial, the jury

convicted Probus of complicity to first-degree robbery, complicity to first-degree

burglary, two counts of complicity to first-degree wanton endangerment, and of

being a persistent felony offender, recommending a total sentence of 45 years’

imprisonment, which the trial court imposed.

II. ANALYSIS.

A. The trial court correctly denied Probus’s motion for a directed verdict.

Probus’s first allegation of error is that the trial court should have

granted his motions for directed verdict on the complicity to first-degree

robbery, complicity to first-degree burglary, and complicity to first-degree

wanton endangerment charges. Specifically, Probus argues that the

Commonwealth offered insufficient evidence that the gun with which Slinker

threatened Robinson constituted a “deadly weapon” or “dangerous instrument,”

the necessary findings the jury had to make to find Probus guilty of those

crimes under the jury instructions. That this issue is preserved for our review

is undisputed.

“On appellate review, the test of a directed verdict is, if under the

evidence as a whole, it would be clearly unreasonable for the jury to find guilt,

only then is the defendant entitled to a directed verdict of acquittal.”2 Probus

asks this Court to find that the jury’s finding of guilt on Probus’s charges was

clearly unreasonable, specifically, because there was insufficient evidence to

2 Commonwealth v. Benham, 816 S.W.2d 186, 187 (Ky. 1991) (citing Commonwealth v. Sawhill, 660 S.W.2d 3, 4-5 (Ky. 1983)).

5

believe the gun Slinker used to threaten Robinson during the commission of

the crime was a “deadly weapon” or “dangerous instrument.” We decline to find

so.

Under the jury instructions, for the jury to have found Probus guilty, it

needed to find, among other elements, that the commission of the crimes

involved a “dangerous instrument,” for complicity to first-degree robbery, and a

“deadly weapon,” for complicity to first-degree burglary and first-degree wanton

endangerment. Probus admits that this Court in Johnson v. Commonwealth

observed that “a jury could reasonably determine that a pellet or BB gun was a

deadly weapon (i.e. a type of weapon from which a shot could cause death or

serious physical injury) in light of history of serious physical injuries caused by

BB or pellet guns.”3 Probus argues here that the evidence adduced at trial as to

the type of gun brandished during the commission of the crime was insufficient

for a jury to find that the gun constituted a “dangerous instrument” and

“deadly weapon.” But Probus’s argument is meritless.

The gun brandished by Slinker was referred to at trial interchangeably as

a “toy gun,” “fake gun,” “BB gun,” “toy BB gun,” and “airsoft gun.” Slinker

characterized the gun at issue most often as a “BB gun.” Probus’s argument

incorrectly assumes that characterization of the gun as a “toy,” “fake,” or any

other less-dangerous-sounding characterization of the gun means that the jury

could have not put those characterizations on the same plane as a

characterization of the gun as a “BB gun,” which this Court has already

3 327 S.W.3d 501, 507 (Ky. 2010) (internal citations omitted).

6

recognized can suffice as a “dangerous instrument” or “deadly weapon.” In

other words, the members of the jury may have equated the characterization of

the gun as a “toy” or “fake gun” with the characterization of the gun as a “BB

gun”—the members of the jury may not have viewed a “toy” or “fake gun”

differently from a “BB gun” in the sense that a BB gun is not typically

considered to equate to a traditional firearm but can still constitute a

dangerous instrument or deadly weapon. Put more simply, who is to say that a

BB gun, not considered to be a traditional firearm, but considered a dangerous

instrument or deadly weapon under our jurisprudence, cannot be referred to as

a “toy” or “fake gun”?

In any event, as we recognized in Johnson, the jury was entitled to

believe that a “BB gun,” which Slinker termed the gun in question to be

numerous times at trial, constitutes a deadly weapon or dangerous instrument.

The trial court did not err in denying Probus’s motion for a directed verdict.

B. Probus’s due process rights were not violated when the Commonwealth allegedly chose to prosecute his case on a different theory than his co-defendant’s, who pled guilty to a lesser offense.

Probus argues that his due process rights were violated when the

Commonwealth characterized the gun at issue in Probus’s case as a deadly

weapon but did not do so in Slinker’s case. While the Commonwealth disputes

the preservation of this issue, the record reveals that Probus did make this

argument to the trial court in his motion for a directed verdict. Even so,

Probus’s argument is meritless.

7

Slinker testified at Probus’s trial that the Commonwealth stated during

Slinker’s guilty-plea colloquy that it was amending Slinker’s charges from first-

degree robbery and burglary to second-degree robbery and burglary because

the gun that Slinker brandished was an instrument that could not be

considered a dangerous instrument or deadly weapon. Probus argues that the

Commonwealth cannot prosecute Probus for complicity to first-degree robbery

and burglary, which requires the involvement of a dangerous instrument or

deadly weapon, when the Commonwealth proceeded against the principal

involved in those crimes on second-degree robbery and burglary for the alleged

express reason that the Commonwealth did not believe the instrument involved

in the crime constituted a dangerous instrument or deadly weapon.

But the only basis for Probus’s argument that the Commonwealth

reduced Slinker’s charges because the gun at issue was not a traditional

firearm comes from Slinker’s testimony at Probus’s trial. This testimony alone

cannot convincingly support the assertion that the Commonwealth had no

other basis for reducing Slinker’s charges than this fact alone. In sum, the

factual basis for Pro bus’s argument is severely lacking, because, even if Slinker

is correct that the Commonwealth reduced his charges based on the

characterization of the gun at issue, the Commonwealth could have reduced

Slinker’s charges for several other reasons.

Moreover, Probus’s argument relies on a fundamentally flawed

assumption—that the Commonwealth cannot proceed against a complicitor on

greater charges than the charges to which the principal pleaded. But an

8

overwhelming majority of jurisdictions hold to be true the opposite of Probus’s

argument—a conviction of a principal based on a plea agreement to a lesser

offense does not preclude the prosecutor from pursuing a greater offense at

trial against a complicitor.4 As the Indiana Supreme Court explained, where the

principal agrees to a plea bargain of a lesser charge and the complicitor is

found guilty at trial of a greater offense, “while both [the principal and

complicitor] have been convicted, we are not presented with two separate

judicial determinations on the merits. Therefore, these convictions do not

present the legal inconsistency which may arise under certain circumstances

in the trials of accessories and principals and which the law must correct.”5 * In

other words:

[Although courts have recognized a necessity for consistency in certain situations in this area, they have done so because of certain assumptions implicit in a finding by a court after a trial on the merits. However, these same assumptions do not arise, nor are the same forces at work, upon an entrance of a guilty plea. When the principal is found guilty after a trial on the merits of a lesser offense than the one originally charged, an assumption may be made that the State failed to adequately carry its burden on the principal’s greater offense. . . . On the other hand, in the situation where a plea to a lesser offense is accepted by a court it cannot be presumed to be a finding of an acquittal of the greater because of the special nature of the plea bargain that often underlies it. The

4 See Donald M. Zupanec, Acquittal of principal, or his conviction of lesser degree of offense, as affecting prosecution of accessory, or aider and abettor, 9 A.L.R. 4th 972 (originally published in 1981, updated weekly); see e.g. U.S. v. Coppola, 526 F.2d 764 (10th Cir. 1975); Oaks v. People, 424 P.2d 115 (Colo 1967); Combs v. State, 295 N.E.2d 366 (Ind. 1973); Jewell v. State, 397 N.E.2d 946 (Ind. 1979); State v. Cassell, 212 S.E.2d 208 (N.C. 1975); Bridges v. State, 263 So.2d 705 (Ala. App. 1972); People v. Hines, 329 N.E.2d 903 (Ill. App. 1975); but see State v. Ward, 396 A.2d 1041 (Md. 1978). 5 Jewell v. State, 397 N.E.2d 946, 948 (Ind. 1979) (citing Combs v. State, 295 N.E.2d 366, 370-71 (Ind. 1979)).

9

very nature of a plea bargain presupposes a restraint by the prosecutor on the punishment to be extracted from the accused.6

Regardless of the Commonwealth’s reason for offering a plea bargain to Slinker,

Probus’s conviction of a greater offense does not violate due process, as Probus

has alleged, because Slinker pleaded guilty to, i.e. was not found guilty at trial

of, a lesser offense. As such, no due process violation occurred.

C. The trial court did not err in allowing testimony regarding Sergeant Whitehill’s commendations and acts of exceptional heroism.

Probus’s next allegation of error was the admission of testimony

regarding Sergeant Whitehill’s commendations and acts of exceptional heroism.

That this issue is preserved for our review is undisputed.

Sergeant Whitehill was the lead investigator. During Probus’s opening

statement, Probus stated that Sergeant Whitehill’s investigation was “sloppy,”

“unprofessional,” and “lazy.” Probus readily admits to this fact. The

Commonwealth called Sergeant Whitehill as a witness. During direct

examination, after inquiring about Sergeant Whitehill’s education, background

in criminal justice, and job history, the Commonwealth inquired about various

commendations that Sergeant Whitehill received over the course of his career.

This led to Sergeant Whitehill to describe in detail three events leading to his

commendations. The defense objected to this testimony on relevancy grounds,

the same grounds on which Probus now challenges the admission of this

testimony.

6 Combs, 295 N.E. at 370-71.

10

“All relevant evidence is admissible, except as otherwise provided[.]”7

“‘Relevant evidence’ means evidence having any tendency to make the existence

of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more

probable or less probable than it would be without the evidence.”8 “Although

relevant, evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially

outweighed by the danger of undue prejudice, confusion of the issues, or

misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, or needless

presentation of cumulative evidence.”9 “The inclusionary thrust of the law of

evidence is powerful, unmistakable, and undeniable, one that strongly tilts

outcomes toward admission of evidence rather than exclusion.”10 “The

language of KRE 403 is carefully calculated to leave trial judges with

extraordinary discretion in the application and use of [KRE 403].”11

“The standard of review on evidentiary issues is abuse of discretion.”12

“The test for abuse of discretion is whether the trial judge’s decision was

arbitrary, unreasonable, unfair, or unsupported by sound legal principles.”13

Probus takes issue with the inclusion of Sergeant Whitehill’s testimony

regarding his commendations and the events giving rise to them. Probus

7 Kentucky Rules of Evidence (“KRE”) 402.

8 KRE 401.

9 KRE 403. 10 Robert G. Lawson, The Kentucky Evidence Law Handbook, § 2.05[2][b] (5th ed. 2013) (citing O’Bryan v. Massey-Ferguson, Inc., 413 S.W.2d 891, 893 (Ky. 1967)).

11 Lawson, supra note 10, at § 2.15[2][b[.

12 Stansbury v. Commonwealth, 454 S.W.3d 293, 297 (Ky. 2015) (citing Clark v. Commonwealth, 223 S.W.3d 90, 95 (Ky. 2007)).

13 Commonwealth v. English, 993 S.W.2d 941, 945 (Ky. 1999).

11

argues that this testimony should have been excluded because of its alleged

irrelevancy and prejudicial impact on the jury.

While the admission into evidence of Sergeant Whitehill’s commendations

and a detailed description of the events giving rise to them could be argued as

pushing the bounds of relevancy and prejudicial effect in Probus’s case, we

cannot say that the trial court abused its discretion in allowing this evidence,

particularly when Sergeant Whitehill’s investigative abilities were placed in

issue by Probus during opening statement. As Professor Lawson notes, the

application of KRE 401, 402, and 403 “embraces not just a tilt toward

admission over exclusion but a very powerful tilt in that direction.”14

Furthermore, trial judges have “extraordinary discretion in the application and

use of” the evidentiary rules of relevancy.15 As such, we decline to hold that the

trial court erred in admitting evidence of Sergeant Whitehill’s commendations

and the events giving rise to them.

D. The admission of evidence of Probus’s purported prior bad acts does not amount to reversible error.

Probus next takes issue with the inclusion of two different pieces of

evidence that purport to constitute evidence of prior bad acts that he argues

should have been excluded. The parties dispute the Court’s ability to review

this issue.

The first piece of evidence in dispute is the testimony of Steven Vaughan,

the individual who purportedly committed an attempted robbery of Billy’s * 12

14 Lawson, supra note 10, at § 2.15[2][b].

15 Id.

12

residence with Probus before the events giving rise to this case. Probus

complains about the admission of Vaughan’s testimony describing Probus’s

drug use, which Vaughan discussed in response to the Commonwealth’s

inquiring about the relationship between Vaughan and Probus. After Vaughan

made two separate and unsolicited statements alluding to Probus’s drug use,

Probus objected; and the trial court asked counsel to approach the bench. After

discussion, the trial court, as agreed to by both the Commonwealth and

Probus, brought Vaughan to the bench and told him to refrain from mentioning

Probus’s alleged drug use.

After Vaughan finished testifying, the parties discussed the matter in

chambers. Defense counsel stated that Probus was angry that defense counsel

did not request a mistrial based on Vaughan’s testimony about Probus’s

alleged drug use. Defense counsel, however, did not believe the inclusion of

Vaughan’s testimony rose to the level of prejudice warranting a mistrial. The

trial court then asked defense counsel if he wanted an admonition to the jury,

but defense counsel specifically declined that request, believing that an

admonition would do more harm than good. The trial court then stated for the

record that it was denying any motion for a mistrial.

We have addressed this scenario before: “If an admonition is offered in

response to a timely objection but rejected by the aggrieved party as

insufficient, the only question on appeal is whether the admonition would have

13

cured the alleged error.”16 The presumption that an admonition can cure a

defect in testimony is “overcome in only two situations: (1) when an

overwhelming probability exists that the jury is incapable of following the

admonition and a strong likelihood exists that the impermissible evidence

would be devastating to the defendant; or (2) when the question was not

premised on a factual basis and Svas “inflammatory” or “highly prejudicial.””’17

To start, nothing about the Commonwealth’s questioning prompted

Vaughan’s statements about Probus’s alleged drug use—Vaughan voluntarily

made these statements in his account of how he and Probus met and in a

description of their relationship. In addition, no doubt an admonition could

have cured the potential for error here. Nothing about Probus’s alleged drug

use had any real impact on the case apart from the stigma the jury may have

assigned to Probus upon hearing he used drugs. More importantly, we fail to

see how the trial court’s instructing the jury to disregard Vaughan’s testimony

about Probus’s alleged drug use could not have cured the admission of that

testimony into evidence. In sum, we cannot find reversible error in the

admission of testimony regarding Probus’s alleged drug use.

The second piece of evidence in dispute is the admission of text messages

sent between Probus and an individual named Danny Ross in the early

morning hours preceding the home invasion, exchanged from 6:15 a.m. to 6:36

a.m. As part of his defense, Probus alleged that he was home sick on the day of

16 Sherroan v. Commonwealth, 142 S.W.3d 7, 17 (Ky. 2004) (citing Graves v. Commonwealth, 17 S.W.3d 858, 865 (Ky. 2000)).

17 Sherroan, 142 S.W.3d at 17 (internal citation omitted) (emphasis in original).

14

the crime. The Commonwealth sought to introduce a text message exchange

between Probus and Ross to counter this allegation. Probus objected to the

introduction of these text messages. Probus and the Commonwealth engaged in

a lengthy bench discussion about them. This culminated in both parties going

through the text messages line-by-line and agreeing to what was to be

redacted, which was approved by the trial court.

Probus now claims that the introduction of the text messages that he

agreed to be admitted into evidence was error. But, “(i]t has long been the law

of this Commonwealth that an error will not be reviewed on appeal if the trial

court has not had an opportunity to rule on the objection.”18 Although Probus

initially objected to the admission of the text messages, he then came to an

agreement with the Commonwealth, with approval by the trial court, as to the

exact content that was to be admitted.

While the Commonwealth is correct in arguing that Probus has waived

this issue for review on appeal, we must still review this alleged error for

palpable error.19 Palpable error requires a showing that the alleged error

affected the “substantial rights” of a defendant, where relief may be granted

“upon a determination that manifest injustice has resulted from the error.”20 To

find that “manifest injustice has resulted from the error,” this Court must

conclude that the error so seriously affected the fairness, integrity, or public

18 Commonwealth v. Petrey, 945 S.W.2d 417, 419 (Ky. 1997) (citing Kentucky Rules of Criminal Procedure (“RCr”) 9.22; KRE 103(a)(1)).

19 Petrey, 945 S.W.2d at 419.

20 RCr 10.26.

15

reputation of the proceeding as to be “shocking or jurisprudentially

intolerable.”21

We can definitively say that the inclusion of the content of the

complained-of substance of the text messages did not rise to the level of

palpable error to require reversal. The complained-of content of the text

message exchange is as follows:

Probus: Cmere before u go to work I have to ask u a ? Bout the FBI coming here soon. Ross: F*** U AND FBI. . . A1NT GOT TIME FOR IT Probus: Well u will then they run in Probus: When they do run in I’m tellin them u useally carry a gun so they tase the s*** outta u Ross: Ir f***** stupid. . . I won’t be here anyway. . . some people work Probus: I’m sure they 11 grab u both from work Ross: Nope. . . no reason. . . ain’t done s*** to worry bout it Probus: Ok Probus: Ohhh believe me by Monday morning I have a feeling that lots of running will b taking place. . . I tried to warn ya. . . I’m so f***** stupid but nobody expects me to b smart. Ross: Wut u talkin bout. . . what u do Probus: I’ll tell u after work if I get a chance Ross: Well i believe i tryed to and tryed to tell u not to do stupid s*** . . . tell me now. Probus: Cnt. Text messages are saved by AT&T after deleted for 48 hours. Ross: OMG call Probus: Ill tell u later just text me when u get off work u may have to meet me somewhere an get my keys to the house.

Regardless of any purported trial court error regarding the admission of the

content of these messages, we are convinced that any such error did not

amount to palpable error.

21 Martin v. Commonwealth, 2Q7 S.W.3d 1, 4 (Ky. 2006). 16

Probus argues that the admission of the content of these messages

suggested prior bad acts committed by Probus, unrelated to the commission of

the crimes at issue. But a plain reading of the messages casts some doubt

about that assertion. To start, it appears that Probus could be suggesting prior

criminal activity on the part of Ross, not himself. And the messages seem to

reveal an allusion to the crimes that would be occurring later that day, i.e., the

crimes at issue in this case. This also calls into question Probus’s objection to

the introduction of this evidence on relevancy grounds. The basis for Probus’s

argument on this issue is lacking, and as such, we cannot find any purported

error on the part of the trial court that amounts to palpable error.

E. The trial court did not err in admitting evidence of cell phone usage between Probus and Slinker.

Probus’s next allegation of error is the trial court’s admiting into evidence

the exchange of text messages between Slinker and Probus the night before

and the morning of the crimes in question. That this issue is preserved for our

review is undisputed.

Recall that Slinker testified that Probus sent Slinker text messages the

night before and the morning of the occurrence of the crimes in question. In

apparent corroboration of that testimony, the Commonwealth sought to

introduce records evidencing phone calls and text messages made between

Probus and some of the witnesses testifying in this case, including Slinker,

Robinson, and Ross. But the Commonwealth did not introduce the content of

those messages.

17

Probus takes issue with the admission of the records evidencing the

messaging that occurred between Probus and Slinker without the

accompanying content of the messages. More specifically, Probus challenges

the relevancy of the admission of these records because of the lack of its

accompanying content.

As outlined earlier, the application of KRE 401, 402, and 403 “embraces

not just a tilt toward admission over exclusion but a very powerful tilt in that

direction.”22 From Probus’s argument on this issue in his brief, it appears that

Probus only challenges the admission of the content of the phone records

related to evidencing an exchange of text messages between Probus and

Slinker, not between Probus and the others mentioned. Probus’s argument is

meritless.

Probus strongly objects to the inclusion of the records because they lack

the content of the messages exchanged between Probus and Slinker, which,

Pro bus argues, could have been about something completely unrelated to the

crime at issue. Probus argues that the content of the messages was recoverable

and that the Commonwealth’s introduction of the records without the content

was highly prejudicial in violation of KRE 403. But evidence of conversation

occurring between Probus and Slinker the night before and morning of the

occurrence of the crime at issue, coupled with Slinker’s testimony, is highly

relevant because it partly confirms Probus’s involvement in the crime at issue.

22 Lawson, supra note 14, at § 2.15[2][b],

18

If the content of the messages were truly exculpatory, as Probus

suggests, and the content of the messages were, in fact, recoverable, then

Probus also had the ability to recover and uncover the content of them at trial,

which he did not do. More importantly, records of phone calls and text

messages exchanged between Probus and Slinker the night before and morning

of the occurrence of the crimes at issue are relevant to evidencing

communication between the two purportedly main culprits of the crimes at

issue right before the occurrence of those crimes. Again, citing the highly

inclusive nature of the admission of evidence under KRE 401, 402, and 403,

we decline to find that the trial court abused its discretion in admitting this

evidence.

F. No reversible error occurred from the trial court’s exclusion from evidence a photograph showing Probus in the hospital four days after the home invasion and text messages Probus sent friends also purportedly evidencing that fact.

Probus next argues that the trial court erred in excluding evidence that

was purportedly “critical to his defense.” Probus takes issue with the exclusion

of two pieces of evidence: 1) a picture showing him in the hospital with an IV

four days after the crime at issue occurred; and 2) text messages between him

and his friends discussing him being on his way to the hospital. The

Commonwealth does not dispute the preservation of the challenge to the first

piece of evidence but does dispute the preservation of the challenge to the

second piece of evidence.

Regarding the photograph evidence, the Commonwealth took issue with

the introduction of the photograph on hearsay grounds and the fact that the

19

Commonwealth could not challenge the substance of the photograph on cross-

examination. The trial court essentially agreed with the Commonwealth and

ruled that the photograph could not be introduced unless Probus testified. The

trial court also excluded the admission of text messages between Probus and

his friends whereby Probus purportedly informed his friends that he was going

to the hospital.

The characterization of the photograph at issue here as hearsay is highly

questionable. We take note of the following guidance regarding whether a

photograph constitutes hearsay evidence:

A photograph ... is ordinarily not hearsay. However, if the image depicted is a person making an oral or written assertion, or performing nonverbal conduct intended as an assertion, such depiction is hearsay when offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. Thus, a digital recording of an accident scene showing the position of the cars as they came to rest does not raise a hearsay issue. Conversely, a digital recording of the same scene capturing the driver of one car stating that the other driver ran a red light would be hearsay when offered to prove that the other driver ran a red light.23

Regardless of the propriety of the trial court’s rulings regarding the

exclusion of these two pieces of evidence, we can definitively say that any

purported error on the part of the trial court was harmless.

“No error in . . . the admission ... of evidence ... is ground for granting

a new trial or for setting aside a verdict or for vacating, modifying or otherwise

disturbing a judgment or order unless it appears to the court that the denial of

23 Michael H. Graham, Winning Evidence Arguments, § 401:7 (Nov. 2018 update) (internal citations omitted).

20

such relief would be inconsistent with substantial justice.”24 “The court at

every stage of the proceeding must disregard any error or defect in the

proceeding that does not affect the substantial rights of the parties.”25 “[A]

nonconstitutional evidentiary error may be deemed harmless if the reviewing

court can say with fair assurance that the judgment was not substantially

swayed by the error.”26 “[T]he inquiry is not simply ‘whether there was enough

[evidence] to support the result, apart from the phase affected by the error. It is

rather, even so, whether the error itself had substantial influence. If so, or if

one is left in grave doubt, the conviction cannot stand.”27

The evidence that Probus wanted to introduce purportedly supported his

assertion that he was at the hospital four days after the crimes at issue

occurred. Probus’s proffered defense was that he was sick on the day of the

crimes in question, so he could not have committed the crimes. But the

evidence he proffered for such an assertion only supports the fact that he was

sick four days after the crimes occurred. We would be hard pressed to rule that

the jury would have been substantially swayed to believe Probus’s alibi of being

sick on the day of the occurrence of the crimes when all the evidence he

proffered only purportedly showed him being sick four days after the crimes

took place.

24 Kentucky Rules of Criminal Procedure (“RCr”) 9.24.

25 Id. 26 Murray v. Commonwealth, 399 S.W.3d 398, 404 (Ky. 2013) (citing Kotteakos v. United States, 328 U.S. 750 (1946)).

27 Murray, 299 S.W.3d at 404 (quoting Kotteakos, 328 U.S. at 765).

21

Moreover, the evidence against Probus included, but was not limited to:

1) the testimony of Slinker, Probus’s complicitor in the crime, describing in

detail the events of the crimes and implicating Probus; 2) Steven Vaughan, who

admitted to having attempted the first home invasion of Billy’s house with

Probus; and 3) physical evidence connecting Probus to the crime, including

Billy’s girlfriend’s stolen purses and items used in the commission of the crime,

like the walkie-talkies and cellphone jammer, found at Probus’s residence.

Considering the above, we are satisfied that the exclusion of Probus’s

purported exculpatory evidence was harmless error.

G. The trial court did not err when it did not poll the jury after the foreperson apparently reported an apparent mistake regarding Probus’s recommended sentence.

Probus’s last alleged error is one concerning the sentencing phase of his

trial. The preservation of this issue is disputed.

The jury recommended to the trial court a sentence of 20 years each for

the complicity to first-degree robbery and burglary convictions, enhanced to 25

years each as a PFO, to run concurrently, and five years for each of the

complicity to wanton endangerment convictions, enhanced to 10 years each as

a PFO, to run consecutively, for a total of 45 years’ imprisonment. Upon

hearing the jury’s recommendation, the trial court asked both parties if they

wanted to poll the jury, and both parties declined. The trial court then accepted

the jury’s recommended sentence and discharged the jury.

After the jury was discharged, the foreperson approached the bench and

indicated to the trial court that the jury may have made a mistake. Per the

22

record, which is very difficult to hear, the foreperson appears to state that the

jury believed that Probus should serve only 25 years and that the jury was

confused regarding parole eligibility.

Probus filed a motion for a new trial based on the conversation between

the foreperson and the trial court. Although the trial court showed concern

about the situation, the trial court denied Probus’s motion, acknowledging that

this would be an appealable issue and that Probus would get a new sentencing

hearing if the defense was correct in its assertion that the jury was confused

about the sentence.

Probus acknowledges that he may have waived this issue by declining to

request a poll of the jury.28 Having so failed, Probus now asks us to order a

new sentencing phase or, at the very least, order the trial court to conduct an

evidentiary hearing on this matter. The only reason this issue is before the

Court is because the foreperson approached the bench to notify the trial court

of the jury’s possible mistake in the sentence it recommended.

However, “)i]t has long been held that a juror may uphold his verdict but

may not impeach it.”29 “As recently as three years ago, this Court reaffirmed

our commitment to the historic rule prohibiting the use of post-trial juror

statements to impeach a facially valid verdict—a rule, as we said in

Commonwealth v. Abnee, that is ‘firmly rooted in the early years of Kentucky

28 See Mayo u. Commonwealth, 322 S.W.3d 41, 57-58 (Ky. 2010).

29 Grace v. Commonwealth, 459 S.W.2d 143, 144 (Ky. 1970) (internal citations omitted).

23

jurisprudence.”’30 The only two exceptions to this rule recognized by this Court

at this point allow the use of juror testimony to impeach a verdict only when

the testimony “concern[s] any overt acts of misconduct by which extraneous

and potentially prejudicial information is presented to the jury” or to evidence

juror bias.31 Because these two exceptions are not the basis for challenging the

verdict in this case, we decline to revisit Probus’s sentence. Just as in Maras,

“[i]n sum, [Probus’s] challenge is ‘the one form of attack on a verdict that has

always been forbidden in Anglo-American criminal law’: an attempt ‘to probe

[the jury’s] process of deliberation and find out how . . . the jury reached its

verdict.’”32

Outcome: Finding no reversible error, we affirm the judgment.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: