Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 03-24-2018

Case Style:

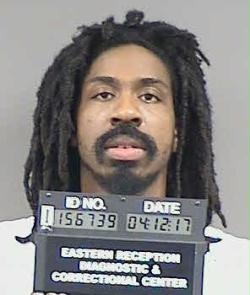

State of Missouri v. Antonio Dixson

|

|

Case Number: ED105514

Judge: Robert G. Dowd, Jr.

Court: MISSOURI COURT OF APPEALS EASTERN DISTRICT

Plaintiff's Attorney: Nathan J. Aquino

Defendant's Attorney: Frederick J. Ludwig

Description: Defendant was charged, along with Aaron Garrison (“co-defendant”), of tampering with a

vehicle by removing the tires without the consent of the owner. At trial, a police officer testified

that around 11:00 p.m. one night while on patrol he received a radio call for tampering at an address

on Virginia Avenue and responded to it. The officer testified that based on information from the radio call he was looking for “two black males,”1 and a silver Dodge Magnum. The officer testified

that when he arrived, he saw a silver Dodge Magnum up on blocks and missing two tires. A black

1 Prior to trial, Defendant moved in limine to exclude references to hearsay statements in the radio dispatch call. The State responded that it would only be offering that evidence to explain the officer’s subsequent conduct when he arrived at the scene. The court ruled that it would allow the officer to testify that he responded to a call for persons in an alley removing tires. When the officer testified that the call referred to “two black males,” defendant objected, and the objection was overruled.

2

Dodge Magnum was parked behind it, and inside the hatchback of the black vehicle were two tires

matching the wheels on the silver vehicle. The building they were parked behind appeared vacant

to the officer. The officer observed two men standing next to the vehicles, Defendant and co

defendant, both of whom are African-American. These men were not doing anything when the

officer arrived; they were just standing there, and they did not run when the officer approached.

The officer did not see anyone removing the tires. The officer asked the two men if they owned

the silver vehicle. They said they did not, and further investigation revealed that the car had been

reported stolen. The owner testified at trial that she had not given anyone permission to take the

tires off. At some point, the officer learned that the black Magnum belonged to the girlfriend of

co-defendant. There were two other people sitting inside that black Magnum. Only Defendant

and co-defendant were arrested for tampering. When asked why the people inside the car were

not arrested, the officer said it was because the radio call had indicated that there were “two black

men removing tires” and that when he arrived on the scene two black men were standing there next to a car with tires removed.2

Defendant’s responsibility for this crime was based solely on the theory that he acted together with co-defendant to remove the tires without the owner’s consent.3 The State argued to

the jury that although the officer did not see anyone removing tires, there was enough

circumstantial evidence from which to infer that these two men removed the tires together. As the

prosecutor put it, tires do not just roll off one car and into another and it is reasonable to infer that

the two people standing near the car were the ones who removed the tires. The defense argued

2 There was no objection to this testimony at trial. The argument that the details of the radio call were unnecessary to explain subsequent conduct was raised again in both of Defendant’s motions for judgment of acquittal at the close of the State’s evidence and all the evidence and again in Defendant’s motion for new trial. 3 Defendant and co-defendant were not tried together. Co-defendant pled guilty to the charges of tampering filed against him.

3

there was no evidence that it took more than one person to remove these tires, and the only person

the State possibly connected to this crime was co-defendant because it was in his girlfriend’s car

that the removed tires were found. Defense counsel argued that Defendant was merely present

and there was no evidence that if someone did assist co-defendant it was Defendant. The jury

found Defendant guilty, and he was sentenced as a prior and persistent offender to four years’

imprisonment. This appeal follows. We address Defendant’s points out of order.

In his second point on appeal, Defendant contends the officer’s testimony about the

contents of the radio call—that there were “two black men” or “two black men removing tires” —

was inadmissible hearsay and should have been excluded. There are two ways to view this out

of-court statement: (1) they were admissible solely for the purpose of explaining subsequent police

conduct, as the State argues, in which case they could not be used as substantive evidence of guilt,

or (2) they were inadmissible hearsay because they went beyond the scope of what was necessary

to explain the officer’s subsequent conduct, as Defendant contends, in which case they should have

been excluded and could not be used as evidence of guilt. In either case, these statements cannot

be used to prove the truth of the matter asserted therein. The State did not rely on the truth of the

these statements at trial to demonstrate Defendant’s guilt, nor does it argue on appeal that they

should be considered as substantive evidence in reviewing Defendant’s challenge to the

sufficiency of the evidence. Those statements cannot be considered for any purpose other than showing subsequent conduct. 4 See State v. Davis, 217 S.W.3d 358, 360-61 (Mo. App. W.D.

2007). Thus, that evidence does not impact the sufficiency analysis, and Point II is denied as moot.

4 The State agrees on appeal that the statements were only admissible to show subsequent conduct. And although it points out that the defense objections at trial may not have properly preserved this claim of error (because they were raised after the answer and did not state the grounds, or because some of the challenged testimony was invited by testimony elicited on cross-examination), the State does not argue that, as a result, the evidence should be considered in determining the facts. See, e.g., State v. Lebbing, 114 S.W.3d 877, 880 (Mo. App. S.D. 2003) (“where there is no objection, hearsay evidence may be considered by the fact finder in determining the facts”). We would be hesitant to apply such a rule here, where the hearsay nature of the objection was well-known to the court and both

4

In his first point on appeal, Defendant contends there was insufficient evidence to establish

his affirmative participation in this crime because the evidence showed only that he was present at

the crime scene when police arrived. Our review of this point is limited to determining whether

sufficient evidence was presented from which a reasonable juror could find the defendant guilty

beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. Nash, 339 S.W.3d 500, 508-09 (Mo. banc 2011). It is not an

assessment of whether we believe that the evidence at trial established guilt beyond a reasonable

doubt, but whether any rationale fact-finder could have found the essential elements of the crime

beyond a reasonable doubt. Id. This Court does not act as a “super juror” with veto powers and

will not reweigh the evidence; rather, we give great deference to the trier of fact. Id. The evidence

and all reasonable inferences drawn from the evidence are viewed in the light most favorable to

the verdict, and any contrary evidence and inferences are disregarded. Id. at 509. But we will not

supply missing evidence, nor give the State the benefit of unreasonable, speculative or forced

inferences. State v. Allen, 2017 WL 4247998, *4 (Mo. App. E.D. 2017).

parties, where the court had ruled in limine to allow the testimony to explain subsequent conduct, and where the State never relied on that as evidence to establish facts.

While it is clear from the record that the court and both attorneys were aware that this evidence was only being offered and admitted for the limited purpose of explaining subsequent conduct, we note that there was no such instruction explaining that to the jury. As a result, there is a some probability that--although it was not argued this way by the prosecutor--this jury considered the contents of the radio call as substantive proof that there were in fact “two black men removing tires” from the car and based its guilty verdict in part on an inference that Defendant was one of them. This is especially likely given the lack of other evidence connecting Defendant to this crime, as discussed herein. See State v. Robinson, 111 S.W.3d 510, 512-14 (Mo. App. E.D. 2003) (describing prejudicial impact when officer goes beyond scope of what is necessary to explain later actions in case without other overwhelming evidence of guilt and where no limiting instruction given to jury). We continue to advise that the best practice when an officer’s subsequent conduct must be explained is to omit the substance of any out-of-court statements on which the officer acted, thus avoiding the need for a limiting instruction or any hearsay or confrontation clause problems. See State v. Watson, 391 S.W.3d 18, 24 n.2 (Mo. App. E.D. 2012). As we have said before, it is often “more than sufficient” context for the officer to simply testify that he or she acted “upon information received.” State v. Boykins, 477 S.W.3d 109, 113 (Mo. App. E.D. 2015).

5

The evidence in this case proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the crime of tampering

occurred because the tires were removed without the owner’s permission. But there was no direct

evidence as to who committed the crime, and the State relied—as it is permitted to do—on

circumstantial evidence to support its theory that Defendant and co-defendant together removed

these tires. To support Defendant’s accomplice liability for that crime, the State was required to

prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Defendant affirmatively participated in committing it. Any

affirmative act, even mere encouragement, is enough. State v. Burrage, 465 S.W.3d 77, 79 (Mo.

App. E.D. 2015). While mere encouragement is enough, mere presence at the scene of a crime is

not enough to show affirmative participation. State v. Barnum, 14 S.W.3d 587, 591 (Mo. banc

2000); see also State v. Brockman, 34 S.W.3d 400, 403 (Mo. App. S.D. 2000). Presence at the

scene can give rise to an inference of affirmative participation only when combined with other

circumstances connecting the defendant to the crime: namely, his association with the others

involved in the crime before, during and after the offense and his conduct before and after the

offense, such as his flight from the scene or his attempts to conceal crime. See In Interest of S.B.A.,

530 S.W.3d 615, 625 (Mo. App. E.D. 2017). “However none of these factors alone is enough to sustain a conviction.”5 State v. Townsend, 810 S.W.2d 726, 727 (Mo. App. E.D. 1991). Thus, as

a matter of law, the inference that a defendant participated in a crime cannot be drawn—even

though such an inference would be in the light most favorable to the verdict—if the only evidence

at trial is that the defendant was present at the crime scene.

That is the case we have here. Defendant was at the scene of a crime, standing near the car

that had been tampered with and the car that the removed tires were found in, along with co

5 The jury here was given the proper instruction on this law based on Missouri Approved Instruction-CR 3d 310.08. The instruction stated: “The presence of a person at or near the scene of an offense at the time it was committed is alone not sufficient to make him responsible for the offense, although his presence may be considered together with all of the evidence in determining guilt or innocence.”

6

defendant. There was no evidence that Defendant and co-defendant knew each other and no

evidence that they were together prior to or during the crime. We cannot supply this missing

evidence by drawing an inference that because he was there, Defendant must have known co

defendant or been with him during the crime or before. Even if that were a reasonable, unforced,

non-speculative inference, it would still be derived from his presence. Thus, reliance thereon

would be contrary to the law that mere presence alone is not enough to sustain a conviction.

Likewise, the fact that the removed tires were found in the back of the black car, which was owned

by co-defendant’s girlfriend, gives rise to an inference that co-defendant was connected to the

crime. But because there was no evidence that Defendant knew co-defendant, his girlfriend or the other people in the car,6 to infer a connection between Defendant and the car requires reliance

again on his presence in the same place as co-defendant and the car.

In addition to no evidence that Defendant associated with co-defendant or the others, there

was also no evidence about Defendant’s conduct before or during the crime. In fact, the only

evidence of his conduct is that when the officer arrived after the crime, he and co-defendant were

“just standing there,” not doing anything with either of the cars, and neither of them ran when the

officer approached. This is the opposite of the type of post-crime conduct—flight from the scene

and attempts to conceal crime—that our courts have said can be used, in combination with

presence, to draw a reasonable inference of affirmative participation. Similarly, the State’s

suggestion at trial that two people must have been involved in removing these tires is not based on

any facts in the evidence. There was no testimony about what is required to remove tires from one

car and put them into another car’s trunk, and while they certainly do not roll off of one and into

6 The officer was asked at trial if the people inside the car “indicate[d] they knew defendant or the other person,” and he said “I believe so,” but an objection to that testimony was sustained. That vague testimony, even if the objection had been overruled and the testimony allowed, could not be relied on to show Defendant’s companionship with any of these people.

7

another car themselves, there was nothing in the evidence to suggest it required more than one

person. Again, to infer that Defendant was one of the people would be based solely on his presence

at the scene. The State also points to the fact that the crime occurred in a vacant lot in the middle

of the night. The late hour, the fact that it was dark and that the crime occurred behind a vacant

building gives rise to the inference that whoever committed the crime was trying to avoid detection.

But to ascribe any of that to Defendant requires reference back to and reliance on, again, his

presence at the scene. It would be improper to rely on an inference that because he was there in

the middle of the night in a vacant ally, he must have been up to no good to supply missing evidence

of Defendant’s conduct.

No matter how reasonable the above inferences are and no matter what light we construe

them in, they stem entirely from the single circumstance that Defendant was present at the crime

scene. Every other piece of circumstantial evidence in this case is only tied to Defendant by virtue

of his presence at the scene: he had no connection to the car where the tires were found, except

that he was standing near it; he had no connection to the tampered with car, except that he was

standing near it; he had no connection with any of the other people on the scene, except that he

was standing near one of them; and he had no connection with any other incriminating facts about

the scene, except that he was standing there. As such, all of the inferences on which this conviction

relies are founded in his presence and not any other evidence of affirmative participation. These

are precisely the inferences our courts prohibit: simply because a person is present, even under

highly suspicious circumstances and where a crime has clearly occurred or is occurring, does not

without more give rise to an inference that the person participated in the crime. The additional

circumstances beyond mere presence needed to support an inference of affirmative participation—

namely, companionship with the co-defendants or evidence of the defendant’s conduct—must be

8

something more than inferences derived solely from mere presence. Otherwise, the conviction

would still ultimately be based on mere presence.

Our review of cases in which the convictions relied on circumstantial evidence to prove

accomplice liability reveals that substantially more evidence than we have here is required for our

courts to say that a fact-finder could infer affirmative participation. The cases affirming those

convictions all involve significantly more than mere presence. For example, in In Interest of SBA,

this Court found that, in addition to the juvenile’s presence at the scene of a fight between two

groups of boys, there was evidence that he and the other boys involved were all together when the

fight was initiated, the juvenile fought with other boys and he was there when the victim was

injured, but he made no effort to assist the victim and instead fled from the scene with the

accomplices. 530 S.W.3d at 625-26. Similarly, in State v. Nance, the defendant was with the

accomplice immediately prior to the assault, he was present at the scene throughout the attack on

the victims and he fled the scene afterwards. 880 S.W.2d 578, 580 (Mo. App. E.D. 1994). In State

v. Carter, the defendant’s active participation in the robbery was inferred from his friendship with

the co-defendants and the fact that he was found with the co-defendant in a car minutes after the

robbery was committed with the stolen money on a seat between them. 849 S.W.2d 624, 627 (Mo.

App. W.D. 1993). Similarly, in State v. Parsons, the defendant’s affirmative participation in

stealing several items was based on his association with accomplices the night before the crime,

his presence in a car the accomplices stole, his flight from the scene when that car crashed and the

fact that he was found hiding under a pile of clothes with the stolen items. 152 S.W.3d 898, 904

05 (Mo. App. W.D. 2005) In State v. Puig, the court found that, although the defendant did not

participate in the physical exchange of money and drugs, there was sufficient evidence from which

his participation could be inferred because he was present throughout the sale negotiations and

9

provided a scale necessary to weigh the drugs and complete the transaction. 37 S.W.3d 373, 376

(Mo. App. S.D. 2001). Similarly, in State v. Dotson, affirmative participation could be inferred

from the defendant’s presence before, during and after the drug sale and the fact that he also

directed purchasers “if you want the pot, follow us outside.” 635 S.W.2d 373, 374 (Mo. App.

W.D. 1982).

Even those cases in which our court have reversed convictions, there was more evidence

of affirmative participation than we have in this case. For example, in State v. Brockman, the

defendant was present at a home where meth manufacturing paraphernalia was seized from the

yard and from several cars on the property. 34 S.W.3d 400, 403 (Mo. App. S.D. 2000). There

was evidence in that case, unlike here, that the defendant knew the owner of the home and the

other people present the day of the search and seizure and also had stayed at the home on occasion.

Id. There was also evidence he was thinking about buying one of the cars from which evidence

was seized, which was at least some connection to that car, unlike here. Id. Nevertheless, on

appeal, the court found that the evidence failed to show the defendant took a sufficiently active

role in the manufacture of methamphetamine, in part because the testifying officer did not know

if the defendant was even present at the time the manufacturing was going on, much less what

steps of that process he may have participated in. Id. In M.A.A. v. Juvenile Officer, the court

concluded there was insufficient evidence to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that the juvenile

affirmatively participated in stealing an MP3 player. 271 S.W.3d 625, 630-31 (Mo. App. W.D.

2008). Even though the evidence showed that, unlike here, the juvenile was with a group of boys

before, during and after the crime there was no evidence that the group of boys had planned to take

the MP3 player or that any of the boys encouraged the boy who actually took the MP3 player to

do so.

Outcome: Here, there is only one of the circumstances our courts require to show affirmative

participation, Defendant’s presence. A conviction cannot, as a matter of law, be supported by that

fact alone. See Barnum, Brockman, Interest of S.B.A., Townsend, supra. Unlike the above cases,

there is no evidence of companionship with co-defendant and no evidence of his conduct prior to

the police arriving. To conclude that Defendant affirmatively participated here would require

drawing a series of inferences—all of which derive solely from Defendant’s presence—and then

stacking them together to supply that missing evidence. While stacking inferences is not

prohibited, we have nonetheless expressed our skepticism of convictions dependent entirely on

inference stacking. See State v. Anderson, 386 S.W.3d 186, 193-94 (Mo. App. E.D. 2012).

Moreover, inferences must be reasonable, non-speculative and not forced; they must also have

sufficient factual foundation and be strong enough to support a finding of guilt beyond a reasonable

doubt. See Allen, 2017 WL 4247998 at *4; see also State v. Putney, 473 S.W.3d 210, 220 (Mo.

App. E.D. 2015). Even if the inferences here were not speculative or forced, but reasonable ones

we must accept because they are favorable to the verdict, they nevertheless all derive from the fact

of his mere presence. That is insufficient evidence on which to sustain this conviction.

Point I is granted. The judgment is reversed, and the conviction and sentence are vacated.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: